What Is Putin Up To in Syria?

Russia and the U.S. are coming into conflict, even as they claim to be fighting the same enemy.

At home the American president is beset by questions about his ties with Russia. But in Syria, U.S.-Russian ties are unraveling. On Monday, after a U.S. fighter jet shot down a Syrian warplane for the first time in the civil war, the Russian Defense Ministry suspended a hotline for avoiding unintended conflict with the U.S. military in the crowded skies over Syria. And it didn’t stop there. The ministry announced that “all flying objects” belonging to the U.S.-led coalition in Syria “detected west of the Euphrates” river will now be “followed by Russian air-defense systems as targets.” In other words: You tread on our turf, and we just might tread on yours.

It’s an odd time for relations to be fraying, because the Russian government has spent the past few days boasting about the kinds of achievements that Donald Trump dreamed of in advocating a counterterrorism partnership with Russia. First the Russian Defense Ministry announced that it had killed dozens of ISIS field commanders and perhaps hundreds of the group’s fighters in airstrikes near the Islamic State’s Syrian capital of Raqqa in late May—and that it was investigating whether Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the leader of ISIS, was among the dead. Then the Russian military reported that it had killed two additional ISIS field commanders and nearly 200 fighters earlier this month in airstrikes in the Deir Ezzor region of eastern Syria.

The Russians seem to be “trying to change the narrative of their intervention in Syria to actually doing what they’ve been saying they’ve been doing, but not, for two years”: fighting terrorists, said the Atlantic Council’s John Herbst, who co-authored a report last year on how Vladimir Putin’s war has primarily involved defending Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. (The Russian government argues that all forces opposed to Assad are “terrorists,” but it’s been focusing on anti-government rebels—including factions supported by the United States—rather than ISIS.)

So what explains Russia’s sudden attention to ISIS—and why hasn’t it translated into better relations with the United States?

Genevieve Casagrande, a Syria analyst at the Institute for the Study of War (ISW), has one deeply skeptical theory. She’s not entirely convinced that the Russian airstrikes occurred, let alone that they took out Baghdadi and could signal a shift in Russia’s involvement in the civil war. “The vast majority of Russian airstrikes inside Syria have targeted the Syrian opposition” to Assad, Casagrande told me, and the Kremlin has repeatedly released disinformation about who they’re targeting—be it civilians or moderate rebel forces.

Casagrande’s organization maps Russian strikes in Syria by gathering official statements, on-the-ground accounts, and open-source intelligence. “We will collect airstrikes that have 20 to 30 different reports of what the airstrike was, what it hit, photos of the plane, accounts about the high-pitched sound of the plane or how many [planes] were flying in the group, etc.,” she said. And ISW researchers have seen only “fairly minimal” evidence so far of a Russian strike near Raqqa on May 28, the day when the Russian military claims to have maybe killed Baghdadi. “It doesn’t mean it didn’t happen,” she acknowledged, particularly since ISW’s network of activists is thin in that region of Syria. But at this point, “it’s a rumored strike for us at best.” (U.S. officials have similarly been unable to confirm the reports, and some activist groups have described a strike in the area in ways that differ substantially from the Russian account.)

“Russia is not in Syria to defeat ISIS,” Casagrande said, even though ISIS has attacked Russians and poses a serious threat to the country. Russia is in Syria to prop up its ally, the Assad government, and by extension to maintain its geopolitical influence in the Middle East and military presence on the Mediterranean Sea. Despite losing their stronghold of Aleppo in December, opposition fighters—not ISIS—are still the greatest threat to the Assad government and thus to the Russians, she argued.

“Russia likes to portray itself as this marvelous counterterrorism actor that is in parallel and in lockstep with the U.S. against ISIS,” Casagrande said, in part because doing so positions Russia as a critical player in providing security in the Middle East. As my colleague Julia Ioffe has noted, Russia has cultivated an image as the West’s indispensable ally on counterterrorism at least since September 11, 2001. But “Russia typically only goes after ISIS when it is convenient for Russia,” according to Casagrande.

In fact, there appears to be a pattern: Russia pounds Syrian rebels and then helps broker some sort of temporary ceasefire, during which it prepares for the next offensive against opposition fighters and targets ISIS. In February 2016, for example, Russia helped arrange a short-lived “cessation of hostilities” in the country. The next month, it assisted the Syrian government in driving ISIS out of the ancient city of Palmyra. By the fall, it was engaged in a massive military campaign to retake Aleppo from the rebels.

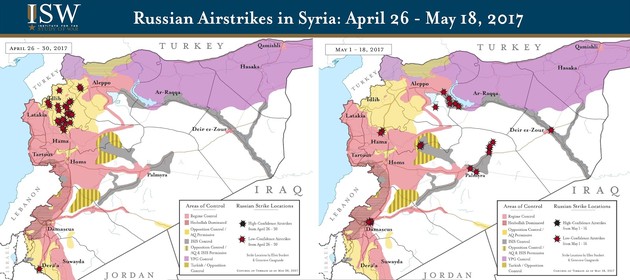

In the lead-up to the latest Russian pivot to ISIS, on May 4, Russia, Turkey, and Iran agreed to establish several “de-escalation zones” in Syria. Consider the ISW maps below, which show suspected Russian airstrikes in the country in late April (on the left) and early May (on the right). In late April, before the de-escalation deal, ISW documented a cluster of Russian strikes in the Idlib region (the yellow terrain) where opposition fighters, including some jihadist groups, are concentrated, and no Russian strikes in ISIS territory. In early May, after the de-escalation deal, ISW recorded an abrupt shift: Russia conducted a number of strikes in ISIS territory, which is depicted in gray in the maps below.

Russia, Casagrande added, may also be bombing ISIS as part of a larger effort to carve out a sphere of influence in Syria once the terrorist group, which is fast losing territory in both Syria and Iraq, is uprooted. Military advances against ISIS have recently sparked a fierce scramble among major powers—especially Iran, Russia, Turkey, and the United States—to assert and protect their interests, bringing these powers into conflict. The Trump administration, for instance, has dramatically escalated America’s confrontation with the Assad government since striking a Syrian air base over a chemical-weapons attack. In May, the United States bombed a pro-Assad military convoy that strayed too close to a U.S. base for anti-ISIS operations in southeastern Syria. On Sunday, it downed a Syrian aircraft that was bombing U.S.-backed anti-ISIS fighters in northern Syria.

Russia, which has the most sway in western Syria, “is using this moment to force-project out east—to remind the U.S. that Russia remains a viable actor in Syria that the U.S. will have to shape policy for,” Casagrande said.

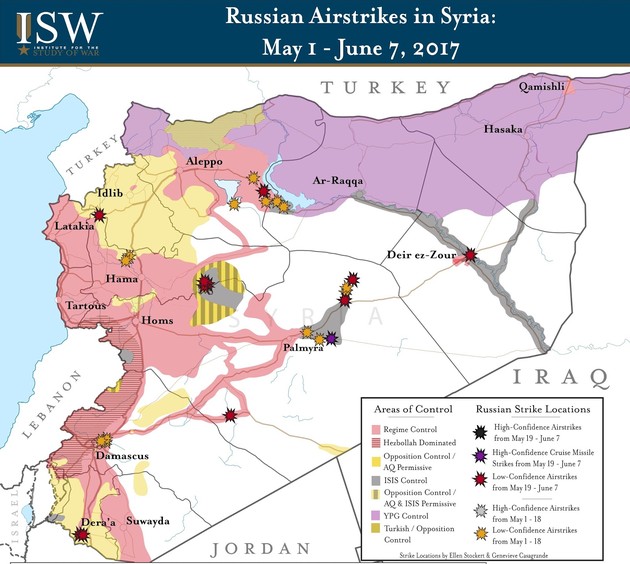

In this context, Russia’s strikes against ISIS in recent weeks can be viewed as a way to constrain the United States and its allies in northeastern and southeastern Syria. In the map below, Casagrande noted, the United States has the most influence in the purple zone, where Arab and Kurdish ground forces are staging an offensive against ISIS, while Turkey has the most influence in the yellow zone, and Russia, Iran, and the Assad government have the most influence in the pink zone.

Even if Trump and Putin suddenly decide to team up in the fight against ISIS, U.S. laws currently prohibit American forces from directly coordinating with Russian forces in Syria, Simon Saradzhyan, a Russia expert at Harvard’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, told me. “As much as Russia would want to expand cooperation with the U.S. on Syria—and I believe Moscow does want to do so because that’d help to normalize [the U.S.-Russia] relationship—I doubt we will see a qualitative improvement in the ways the U.S. and Russia interact” in Syria, he wrote by email.

The military campaign against ISIS, Casagrande explained, is “not just about clearing terrain—it’s about how you clear the terrain and what local structures you set up after the fact.” And therein lies the problem: Russia and the United States share an enemy in ISIS. But they remain at odds over what comes after the Islamic State.